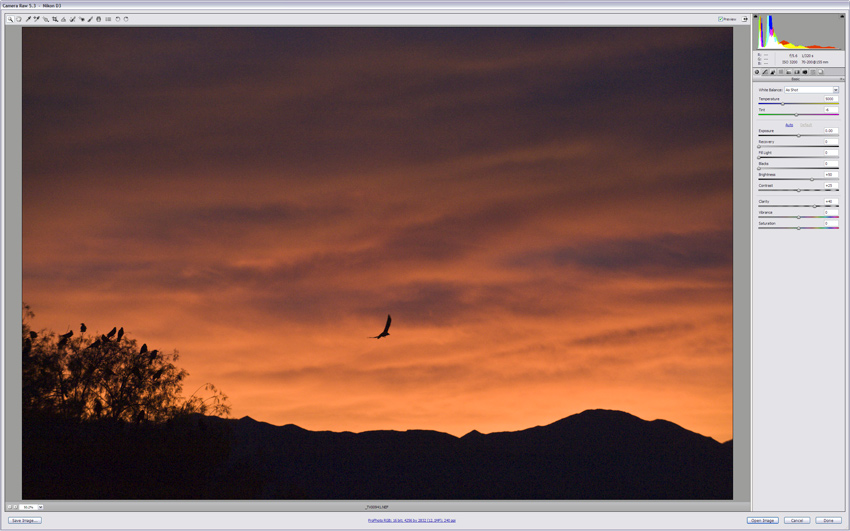

When you first open a properly exposed Raw image, it usually looks flat and lacks punch. It’s nothing at all like you saw when you clicked the shutter. That image now requires processing in Photoshop’s Adobe Camera Raw (ACR), Lightroom, or the Raw converter of your choice. You can, and should, adjust the exposure, set the global white balance, capture sharpen, handle noise, etc., in ACR or its equivalent, but a discussion of Raw processing will be for future posts. For now, in general, just make sure you leave some room at the dark and light ends of the histogram, if possible, and leave the image a little flat to open in Photoshop. It’s always easier to add than to remove contrast and saturation in your final Master image.

So, what is the difference between contrast and saturation, and how do you add one, the other, or both?

Contrast is the difference between light and dark tones. You can also think of it as the separation between the shadows and highlights. An image with low contrast is said to look flat or dull, while high contrast makes an image look punchy or “contrasty”.

Saturation is the depth or intensity of the color. The lower the saturation, the less intense are the colors. They can look weak and pale. If you fully “desaturate” the colors, you end up with a monochrome, or black & white, image. On the other hand, if you increase saturation too high, the colors can become “oversaturated” and look unnatural.

To illustrate the effects, let’s use an example from Antelope Canyon. As you may know, Antelope Canyon was created by erosion of the Navajo Sandstone. As sunlight streams in from the top, it both reflects and directly illuminates the intricate walls and surfaces in the narrow canyon. With your camera’s white balance set on Auto, the prevalent orange hue becomes sort of a grayish orange in the Raw image.

We’ll start with the unprocessed Raw image, shown below. As you can see, it’s rather flat and dull.