At a workshop in Redwood National and State Parks back in 2003, Jack Dykinga gave me one of the best pieces of advice I’ve ever received for getting better images in the field: Use a focusing cloth. It was simple, had been around just about as long as photography itself, yet was rarely used by anyone but large format shooters. I adopted it back then for use with my DSLR, and have been using it ever since. For me, it has become as essential as my tripod and cable release.

It helps me compose and focus, both physically and mentally. With it, I can easily see anything on my LCD, regardless of the ambient light. It helps keep wind, sprinkles, and even flying bugs out of my eyes while I’m shooting, helping me concentrate on my subject. With it, it’s much easier for me to check the corners and edges of my frame, and to look for merges throughout the image. It even allows me to use the Depth of Field preview function, regardless of how dark the image becomes when I push the button!

It’s become so important to me, that I bring a spare when I travel in case something happens to the first one in the field. And as a final bonus, many of my shooting buddies have encouraged me to use it all the time—even when I’m not shooting. They say it’s a fantastic fashion accessory that looks great over me.

My original focusing cloth, also known as a dark cloth, was a 36″x48″ Toyo-View focusing cloth that I got from B&H. After using it for a few years, I wanted something waterproof, breathable, darker, and more versatile. Besides, B&H no longer carried the Toyo-View cloth. After six months of testing various combinations of fabrics and Velcro placements, I now use my own Tom Vadnais Photography 36″x48″ waterproof focusing cloth. It’s an improved design that’s handmade right here in the USA, and is available only from me. Please e-mail me at tom@tomvadnais.com if you’re interested in ordering one directly (US$84 + US$5 shipping and handling to a US address). It’s black on the inside, to give you a dark area to shoot from, and white on the outside to reflect heat. There are strips of Velcro on both sides of one end that cinch the cloth around your lens, making it fast and easy to attach and remove when changing lenses in the field.

Focusing Cloth in the Field

After wrapping one end around your lens, the rest of the cloth simply drapes over your camera, your head and shoulders, and partially down your back. This eliminates most of the stray light around you, allowing you to see much better through your viewfinder. You can’t believe how much easier it is to concentrate on your composition and focusing when surrounded by relative darkness. It also allows you to see everything on your LCD, even in the brightest sunlight.

As you can see from the photograph below, it can also help you blend in with any ghosts you may encounter when out shooting.

Focusing Cloth and Ghost

Now, do you have to spend US$84 on a commercially available waterproof dark cloth with Velcro. Of course you do—-if it’s one from me! Not really. A US$5 black bath towel from a discount store works just fine. You can drape the towel over your lens, camera, and head, as my friend Sue is doing during a workshop in the Smokies. (Her towel is dark blue, but is still effective. In general, though, you want a black cloth or towel, so you don’t have any visual color contamination while you’re shooting under it.)

Sue with Dark Towel

Like any other new tool in photography, using a dark cloth takes a little getting used to at first. Think back to when you first used a tripod, remote release, or any filters. But almost right away, you’ll likely find the benefits so outweigh any learning curve that you’ll adopt it full time. I did.

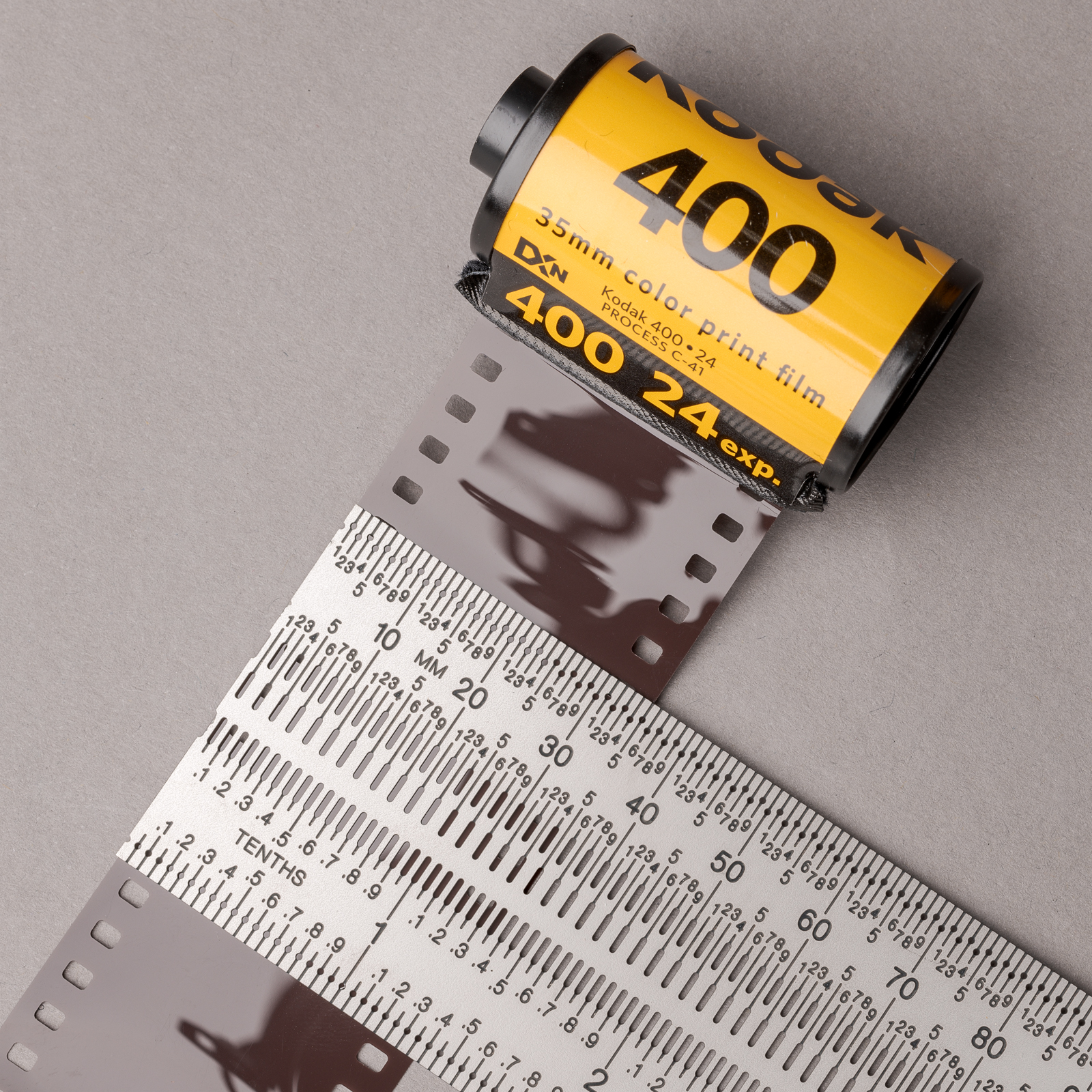

Since all lenses and image sizes are the same between 35 mm film and full frame DSLR cameras, the 35 mm equivalent name is used for full frame DSLRs, even though nothing measures 35 mm in their image frames.

Since all lenses and image sizes are the same between 35 mm film and full frame DSLR cameras, the 35 mm equivalent name is used for full frame DSLRs, even though nothing measures 35 mm in their image frames.