For a time, I was disappointed that so many of the photography enthusiasts I encountered when judging for or speaking to camera clubs, or when co-teaching photo workshops, didn’t seem to take their photography seriously enough (in my world) to want to master post-processing. More than ever before, it seemed, digital photographers were looking for the easy way out when it came to post-processing. I wondered why.

Maybe this harkened back to the color film days, where you mailed or dropped off your rolls of slide or negative film, and then were either pleased or disappointed by the slides or prints you got back. Except for B&W negatives in the wet darkroom, there was no post-processing done by most film photographers. If you weren’t happy with your prints, you could ask the lab to reprint them. That may or may not get you what you envisioned. If you weren’t happy with your slides, you were out of luck. But if the negatives or slides just weren’t right, your only option was to reshoot, if you could.

But it’s all digital now. So maybe it was the steep learning curve for mastering Photoshop. Maybe it was the result of the proliferation of plug-ins promising perfection at the click of a mouse button. Maybe it was short attention spans in a fast-paced society. Maybe it was simply laziness.

Maybe it was none of those.

For me, the beauty of digital photography has always been that you can control every aspect of the creation of an image, from composition and exposure through post-processing for making a fine print.

But wait! What’s this printing thing you speak of?

Here’s where my epiphany occurred.

Few photographers will make any kind of print large enough to frame. Fewer still will ever make a “fine art” print. Many (most?) will never print their images at all. (The last time someone handed you a stack of 4×6 prints of their vacation snaps they probably had live dinosaurs in them.)

Today, even avid amateurs share the majority of their images through social media, or on tablet and smart phone displays, or for the most adventurous, on photo sharing websites like Flickr or a photo club’s online gallery. None of these requires detailed post-processing.

Most photo enthusiasts photograph for the fun and challenge of capturing an image—hopefully one worthy of sharing. Studying the intricacies of Photoshop, with its steep learning curve, can be complicated, time-consuming, even daunting. Does that sound fun? And if it detracts from the reason for photographing in the first place, it could lead to giving up photography for something that doesn’t seem so much like work.

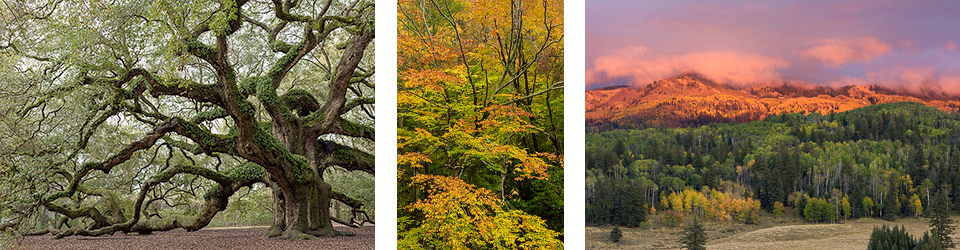

As strange as this may seem to many, I relish the hours spent working and reworking images. I truly enjoy the challenges of trying to get the color and light to be just where and how I want it in the final print. Stranger still, I’m glad that the processing is never perfect, and can be tweaked every time I encounter the image again. (The image below is a culmination of tweaks done over a couple years.) I’m constantly learning new tips, techniques, and tools—all to help me make better and better prints.

But now I realize that the true beauty of digital photography isn’t necessarily that you control every aspect of image making. It’s that you can do as much or as little to your images as you want, depending on why you are photographing.

Right now, digital cameras have improved so much that it’s easy to get good images right from the camera. Many newer cameras even have some post-processing capabilities built-in for additional creative possibilities.

For that next step, free photo editing software (Picasa, GIMP, your camera’s software) allows cropping, resizing, and some image enhancements or corrections to be made without having to spend hours learning in-depth techniques.

Those wanting more options can use programs like Lightroom or Elements. Many plug-ins are available for them to help you easily and quickly modify your images to taste. And for those wanting the most control of their images, there is always full-blown Photoshop.

Not every photograph needs the same level of post-processing. Photos destined only for the web or phone/tablet viewing likely won’t need any. Images for publication in books or magazines often don’t need more than a pass through Lightroom. For fine art prints, careful processing in Photoshop will still yield the best results.

Even in my own photography, I don’t do the same post-processing on every image. For my automotive engineering day job, I do little beyond sorting, deleting, and renaming my images. But for my fine print images, I carefully process every image in Adobe Camera Raw, then Photoshop.

So don’t feel like you’ve got to master post-processing to be a photographer. You have the freedom to choose what is most comfortable for you, and to learn as much about post-processing as your time and interest allows. And if you’re so inclined, there’s always more to learn!

Good insight Tom. I think I agree with you. I sometimes use my willingness to work on an image as kind of a ‘scale’ that measures how good I think the image is. There are images that I make where I can’t wait to work with it in the digital darkroom….others I force myself to at least start…and finally others, after downloading and sorting leave me less than enthusiastic.

I always WANT to be excited to work on the image…..so maybe that should tell me something about taking more time in the field and being more careful in capture. If I would only listen!!!

I’ve always been amazed at what you put into post-processing your images. Of course the results are stunning! I’m slowly working my way through the Charlie Cramer book as time permits but that’s the bugger isn’t it? Time. My struggle is deciding which images are worth the energy to go the extra distance with that limitation.

I am feeling better about the puny post-processing I do on my images that end up on the blog now though. I’ve always felt like I should do more but I think you’ve convinced me I’m doing enough for the purpose they serve.

Cheers! – V